| |

WEST COAST DECORATIVE PAINTERS

Traditional Disciplines Applied with Contemporary Spirit

By Hunter Drohojowska

© Architectural Digest, May 1991

|

In

the rarefied world of contemporary art, the notion of the "decorative" often

meets with disdain. Yet before the modern era, decoration

was considered one

of the primary functions of painting. Embracing rather than

rejecting the styles and skills of the past, a handful of

artists in California have returned to decorative painting.

They have mastered Renaissance realism, trompe-l'oeil illusion

and Japanese naturalism while forging their own individual

styles.

Japanese

and Chinese arts have historically celebrated decoration,

and the influence of the Far East

is evident in the work of three of these painters. Wayne

SMyth says his attraction to Japanese art stems from that

culture's appreciation for harmony with nature. "The

|

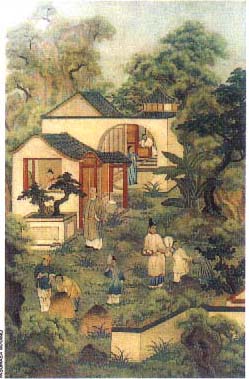

ABOVE:

Robert Crowder of Los Angeles lived in Japan for many years

and studied with the painting master Mochizuki Shunko.

He has worked in the Oriental style for almost 50 years. Photo

by Yasumasa Tanano

|

Japanese

have the ability to improve on nature," he notes. "'More beautiful

than true,' as they would say."

Smyth

worked as an art director before turning to painting. Then in 1979

he was asked to do a pair of screens depicting a Japanese emperor

and empress for Linda Ronstadts's

house

in Malibu. They proved a success, and he started working in a Japanese

style on screens built by his partner, George Lazoraitis. Smyth

points out that in Japan the maker of screens, the hyogushi,

is as respected as the painter.

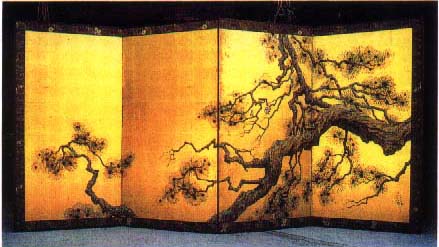

ABOVE: Wayne

Smyth's delicate composition in the Edo-period style is executed

on a four-panel screen made with traditional Japanese methods

by his partner, George Lazoraitis.

|

Lazoraitis builds each screen's framework

from tempered alder wood, covers it with seven layers of mulberry

paper, finishes the front with gold or silver leaf or silk,

and after the image is completed, adds a border of antique

Japanese Brocade and a black-laquered frame. The two artists,

who live in Los Angeles, operate under the name Byobu West

-- from the Japanese word for screen.

|

Smyth

is inspired by Edo-period art, and his screens feature scenes

such as cranes in flight or

evening rains. The effect is Japanese but scaled to meet

the requirements of a Western interior. "We give the client

a traditional subject but in untradtional sizes," explains

Smyth.

Robert

Crowder, also in Los Angeles, has been painting in the style

of the Far East since the

mid-1940s. Before the Second World War, Crowder was teaching

English and music in Tokyo. While there, he studied painting

with the Japanese master Mochizuki Shunko.

|

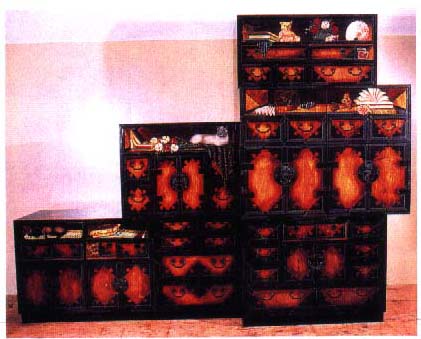

ABOVE:

Best known for her playful adaptations of the traditional Japanese tansu,

Karen Kariya uses her accomplished trompe-l'oeil technique

to create

the illusion of iron hardware and shelves, to which she often

adds a variety of the client's personal possessions.

|

|

Since

his return to this country after the war, he has dedicated

himself to painting, and his command of the Japanese style

is convincing: He was commissioned by Mitsui to decorated

the Japanese Pavilion at EPCOT Center in Florida.

The

Japanese aesthetic is understated and humorous in the work

of Karen Kariya. A third-generation

Japanese American, she counts nineteenth-century American

trompe-l'oeil artists Milliam Michael Harnett and John

Frederick Peto as important influences. She is best known

for her trompe-l'oeil tansu --

chests with touch-latch doors and clever illusions of shelves

and iron hardware. For commissioned works, Kariya will

personalize her pieces by using the owner's name in the titles

of books

she has depicted on the shelves. This sort of coded symbolism

is in keeping with the tradition of trompe-l'oeil. |

|

|